Build to Sell or Build to Last

30 Mins

|

By Team Artha

John Warrillow in Built to Sell

This binary choice or classification may or may not be appropriate. Start-ups can be founded and built with multiple motives, and the manner in which they evolve and eventually exit may or may not have anything to do with the initial intent of the founders.

In hindsight, it may appear that every large company that went on to list on a stock exchange started off with the ‘built to last’ mind-set. Or one might assume that the probability of a start-up with a ‘built to last’ mind-set doing a successful IPO is much higher than a built to sell start-up. This assumption may not be true either, simply because of the fact that it is extremely difficult to take a start-up to IPO even if was built and run as if it would last forever. The probability of a death or acquisition is almost equally likely for both the categories.

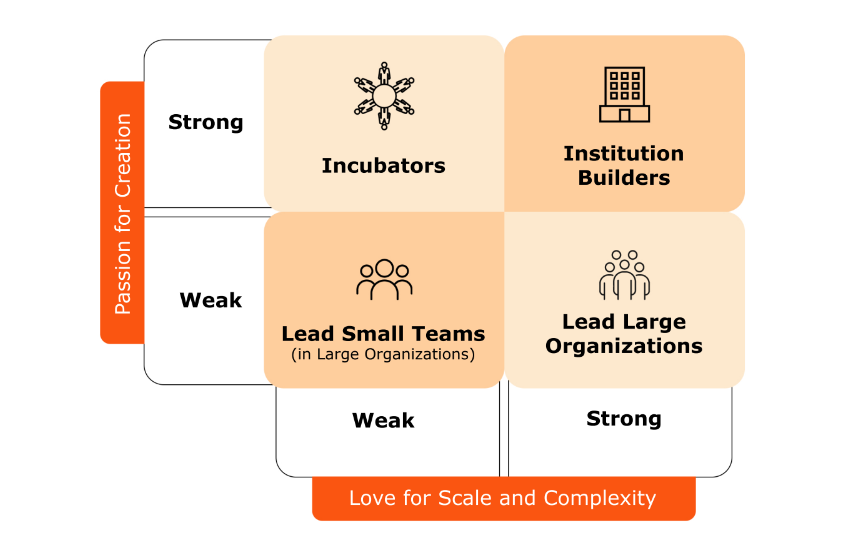

The 2 by 2 below is a good classification of those who build and/or run organizations:

Founders in the top left hand corner are the ‘incubators’. They love incubating new businesses. The motive for this may be two fold, namely, a) building a business around their passion, b) building opportunistically with an eye on selling it. Both may eventually end up selling unless circumstances conspire to keep the founder away from an exit.

Sudeep Kulkarni, co-founder of ‘Tribe Fitness’ and ‘Game Theory’, is deeply passionate about sports and fitness. Fitness was not such a cool thing in India and wasn’t something people liked to talk, or brag, about. Sticking to a fitness programme was one of the biggest challenges that people faced. It just remained one of the forgotten new-year resolutions. Sudeep and his co-founder believed that if people could exercise in a group in a cool facility, fitness could become popular and even fashionable. It turned out exactly as they had envisioned. In 2017, CureFit acquired acquired Tribe Fitness. It had acquired ‘Cult’, a similar start-up, a year back in 2016. The founders of Tribe Fitness and Cult were ‘incubators’. They built their businesses around their passion. They were not the kind of entrepreneurs who loved running complex scale businesses. Running a scale business needs a different set of skills and motives. They realized that the businesses they built could scale better under the CureFit umbrella. So, selling out and going on to pursue their next big dream would be their journey. Sudeep is now busy building his next start-up, ‘Game Theory’, which is trying to bring sports closer to local neighbourhoods.

There is a second category of ‘incubators’.

In the first half of 2018, there were a spate of investments in hyperlocal milk delivery start-ups in India, like Doodhwala, SuprDaily, DailyNinja, MilkBasket, Morning Cart, RainCan, among others. While some of them were into pure play milk delivery, some others quickly diversified to supply a few daily essentials along with the milk. The value proposition was simply the convenience of being able to order at night through an app and having the stuff delivered at the doorstep the next morning.

This was a new service that no organized player had attempted before for the obvious reason of awfully poor unit economics. The margins on milk were wafer thin and could never cover the costs for an organized player. But this did not deter some of these start-ups that saw an opportunity to acquire users who would transact 25 times a month!

These were clearly businesses that were ‘built to sell’. There were no defensible moats and the unit economics on a standalone basis were quite hopeless. It would be very easy for a well-capitalized and established player to bulldoze its way into this space unhindered, and walk away with their business. What these start-ups were banking upon was obviously to rapidly scale this business under the radar and acquire a huge base of loyal customers before some of the big players could take notice. At which point they would be ripe candidates for an acquisition.

But things changed rapidly on the ground. The burn rates for these start-ups continued to be high with no real possibility of improving unit economics. Funding dried up faster than anticipated. Bigger players like Bigbasket acquired three of these players, Morning Cart, RainCan, and DailyNinja, and rapidly scaled the business. By increasing the assortment of daily essentials that could be supplied along with milk, the unit economics suddenly turned around. All the others hyperlocal start-ups in this space have been in frantic talks with potential buyers.

While the ‘build to sell’ category of start-ups are easy to spot, there really is no ‘build to last’.

I believe that there are fundamentally two differences between a ‘build to sell’ approach and all other approaches:

a. the stakeholders being addressed in each of these approaches are the different. A ‘build to sell’ approach is about looking around to discover opportunities that would be interesting to the biggies in the market with deep pockets. These biggies could be large companies or large private equity firms. In contrast, a ‘build to last’ approach is about looking for problems being faced by customers or enterprises and finding sustainable solutions for them,

b. if you use the concept of a founder-idea fit, typically there is none in a ‘build to sell’ approach whereas founders who start with other intents are often passionate about the idea they pick to work on. Some of them do not have a penchant for running it beyond a point and actively scout out for a buyer, while others are happy scaling and growing the business without limits.

In the above example, the hyper-local start-ups were clearly looking at the big daddies of e-commerce like Amazon, Flipkart, Bigbasket or even the food-tech companies like Swiggy and Zomato to buy them out. They knew that these biggies were focused on their core business and had no time to spare for these fringe categories. While these categories may not have made economic sense on a standalone basis, especially in a VC investing context, they would have made eminent sense as part of a broader range of offerings for a bigger e-commerce e-commerce player. Therefore, if they could use this opportunity to rapidly build a business that would be a logical extension for these large companies at a later date, it could fetch them a good price. This could obviously backfire if the biggies chose to organically build this business when they could free themselves a bit.

The decision to sell or continue to operate

Based on an extensive research over a ten year period from 2003-2013, Jason Rowley in an article in TechCrunch (17 May 2017) titled, “Here’s how likely your start-up is to get acquired at any stage” showed that of all start-ups that found a successful exit, about 6% were through an IPO and the balance 94% were through an acquisition. It is very unlikely that 94% of start-ups began their journey with a ‘build to sell’ mind-set. It just indicates that irrespective of the mind-set, the reality is that a predominantly large percentage of start-ups end up getting acquired.

When I joined Daksh, I strongly believed (and the Founders shared the same belief) that Daksh could be the Infosys of the Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) space. For the few who may not know the Infosys analogy, Infosys was one of India’s most highly respected global company built by a bunch of first generation entrepreneurs whose families had no business background. They were bright engineers from India’s premier educational institutions who decided on doing something different and built one of India’s most respected and values driven company. Coming back to Daksh, despite the crowded space, very soon it turned out to be a two horse race – Daksh and Spectramind. Before long Spectramind was acquired by Wipro. We were hoping to continue to grow and go the IPO route. However, over a period of time, the business developed a client concentration. This really means one to three clients are contributing to a disproportionate chunk of the revenue. This is a pretty well-known business risk. If the choice is between developing client concentration by accepting new business versus turning down this business, the decision is a no-brainer. You will accept business any day as long as on a standalone basis it is of good quality. At Daksh, a US telecom major contributed contributed to a large chunk of revenue. At that time, this telecom major was going through its own challenges in terms of how it was perceived by customers in relation to its major competitors. To make matters worse, there were a series of senior leadership exits. The company hired IBM Consulting to help them with a strategic plan to arrest their decline and reposition themselves as a reliable and customer centric service provider. As part of the comprehensive consulting engagement, IBM figured out that it would be helpful to move the telecom major’s customer contact centres from India to the Philippines. Philippines had been a US colony from 1898 to 1946 and the two countries had a lot of cultural similarities. Coupled with the availability of low cost English speaking resources – who spoke in an American accent – Philippines was fast emerging as a destination for customer service outsourcing for American companies. The icing on the cake was that Filipinos were also known to be naturally customer centric.

So, when IBM made an offer to Daksh for an acquisition, we went ahead and signed the deal. After the acquisition, Daksh went on to build one of the biggest customer contact centres in Manila, under the IBM umbrella. Daksh, now a fully owned subsidiary of IBM, helped grow IBM’s BPO business exponentially. Through their technology consulting services, IBM had built deep client relationships with most American corporates and this helped drive business for Daksh from these companies. Daksh no longer needed to go out and sell. IBM sales reps from other lines of business including consulting were cross-selling BPO. This brings us to one important important lesson of whether to sell your business or continue to run it. You should continue to run your business if you believe you can run it better than anyone else in terms of operational rigor, growth, sales & distribution, and customer experience. The moment you believe the business can be better driven by being a part of a larger entity you should be open to an acquisition. The other reality check is that the odds of building an institution that outlasts you are very low and you should deal with this with equanimity.

In another story, Uber chose to sell out to Didi Chuxing in China in 2016 after nearly three years of operations and realizing that all the odds were stacked against them including the Chinese Government’s attitude to foreign companies operating in China. In return Uber got a 15% stake in Didi. By then Uber had burnt through nearly $2 billion of cash. However, the decision to sell turned out to be a smart move. If they had continued, it would mean even more cash burn. With Uber shutting, Didi became a monopoly with better control over pricing. Uber’s stake in Didi some years later was valued at nearly $7 billion. There couldn’t have been a better return on i a better return on investment.

In another story, Virtusa had listed on NASDAQ in 2007. Shortly, Metavante Technologies, a Wisconsin based Technology Company that provided financial technology services, regulatory advice, and consulting to its customers (consisting primarily of small to large sized financial institutions), reached out to Virtusa for an acquisition. It meant taking a public company back to being a private company again. At that point of time, the founder of Virtusa, Kris Canekeratne had run it for nearly eleven years. Kris had always been of the view that one should run a company as if it was built to last and that an IPO was just another milestone. Though it was fashionable to say this, most founders after an IPO, run out of steam and do not have the penchant for running a low growth company in a predictable manner quarter after quarter. There were terrific synergies between Virtusa and Metavante. Talks began in earnest. However, there was a black swan event in the form of the global credit crisis. Talking of black swans, we realized that they are not as rare as Nassem Taleb had made it out to be! Companies of all kinds were shaken up by the credit crisis and most plans went terribly awry. The talks were called off. Virtusa continued to be a public company and Kris continues to run it to this day. Along the way it went on to reach a market capitalization of a billion dollars and more. This is a classic case of how difficult it is to plan an exit, and the value of John Warrillow’s advice that one should always run a company as if it would last forever.

Window dressing

Irrespective of whether it is a build to sell or a build to last case, it is not uncommon for start-ups contemplating an exit to do some window dressing. This is essentially trying to make your company look better than it actually is. In doing this you are hoping that the buyer does not see through and you could obtain a higher price. This is clearly not a good thing. If the buyer discovers even a bit of this or becomes suspicious, they would likely believe that there must be lots more hidden.

Examples Examples of window dressing include trying to boost profitability by deferring essential expenditure or by cutting essential expenditure. Deferring essential expenditure could be about deferring license renewals, putting a hold on hiring, postponing maintenance etc. Some of the cuts may not show up adversely in the short term and the hope is that the buyer won’t see through this. Window dressing could also take the form of adding poor quality customers or revenue. Poor quality customers or revenue could come in many forms. It could be revenue from customers with a high likelihood of default in payments, or non-repeat revenue, or revenue at low price-points (and hence low margins).

Again it boils down to the wisdom that it is always a good idea to continue to build the business as if it would last for ever. Mathematicians say that lying is a wrong strategy from a game theory perspective, besides being morally reprehensible. Similarly, window dressing is a strategy that has a higher probability of hurting your business and personal reputation than doing any good, besides potentially depriving you of a good night’s sleep.

Businesses that are founded with a built to last mind-set have a greater probability of achieving long-term success and creating value for all the stakeholders. The founders and employees at such start-ups are more likely to be motivated and happy because they are working towards a mission. Deep inside there is a sense of self-respect and pride. The culture would be more stimulating and the likelihood of recovering from lows is much higher. Having said this, as we illustrated earlier, the final outcome depends upon a whole host of factors beyond the control of the founders or their investors.

Team Artha